by W.Kirk MacNulty

Kabbalah is a Hebrew word that means reception, or to receive, or that which is received. Used as a noun it refers to the mystical tradition of Judaism. It is certainly the oldest of, and the foundation for, almost all the Western religious disciplines; and we will find its basic metaphysics to be entirely familiar. Traditionally Kabbalah traces its origins to Abraham who is said to have been initiated into its mysteries by Melchizedek, the legendary king who, according to the tradition, had neither father nor mother; and who is associated by some with Enoch and Elijah. Historically, the Kabbalistic principles we will examine are to be found in biblical references and were later incorporated into the Temple rituals.

After the destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 A.D., we find Kabbalah in numerous different formulations at various periods and localities throughout the Jewish diaspora: the charming tales of the Haggadah, the scholarly debates of the Talmud, the Neo-Platonic metaphysics of Medieval Spain, and the labyrinthine Gematria and Notarikon of Renaissance and Post-Renaissance Europe, all contribute to branches of an immense body of literature which speaks of Kabbalah. There are two points which we must observe about this literature.

The first is that none of these things – the content of the Bible, the tales of the Haggadah, the Talmudic arguments, Gematria, Notarikon, even the Tree of Life itself – are Kabbalah. They are the various working methods that have been used by Kabbalists in a wide variety of cultural situations over thousands of years. Kabbalah itself is the set of fundamental principles which underlies all these working methods; or more precisely, it is the insight into those fundamental principles which is received by those who make use of the working methods. It seems to me that many of the books which have been written about Kabbalah, particularly those written in the last century by authors who were not Kabbalists, have tended to identify one or more of the working methods with Kabbalah itself. This is the sort of thing we will seek to avoid by looking beneath the working methods for the principles to which they refer.

The second point we should notice about the variety of styles and idioms which are to be found within the body of Kabbalistic literature is that their very diversity indicates that Kabbalah has been reformulated from time to time to suit the requirements of particular cultures or localities. Because of this practice, the Kabbalistic Tradition has always been available in a form more or less contemporary with, and generally familiar to, the individuals who sought to investigate it. Such a reformulation is in process at the present time, and we will examine the Kabbalistic principles using this new formulation. Although the idiom is contemporary and makes extensive use of the concepts and vocabulary of modem psychology, it is based on traditional material. In particular, it builds on the line of R. Moses Cordovero who worked in Safed in the 16th Century.

NB The reader who wishes to pursue the subject of Kabbalah beyond the very brief introduction in this paper should refer to the writings of Z’ev ben Shimon Halevi.

Cosmology

Like all mystical traditions, Kabbalah begins (and ends) with the Deity. In keeping with the Jewish tradition of which it is an integral part, Kabbalah has very little to say about the Godhead. This policy appears to be derived from the fact that God is without limitation. Therefore, any attempt to describe God must certainly fail; and any attempt to ascribe attributes to God must certainly result in a contradiction. For example, we would certainly agree (no doubt with more than a little hope) that God is merciful. But if we allow ourselves to believe that, we will conclude that God, in Its mercy, might omit to give us exactly what we deserve; and that would be unjust, which for God is unthinkable. To avoid this kind of contradiction, the Kabbalist does not ascribe any attributes to the Deity. God is said to be beyond even existence since existence itself is a concept that we can contain within our limited awareness. The Hebrew word for God is Ayin, which means ‘No Thing’, and Ayin Sof which means ‘Without End’. Beyond that (and a very few other ideas, one of which we will look at below) there is the Rabbinical saying ‘God is God, and what is there to compare with God?’, which sums up the Jewish (and Kabbalistic) point of view very succinctly.

While the preceding notion copes with the transcendent nature of God reasonably well, it does nothing to explain the immanent God, the Deity who is ‘… closer to you than breathing, nearer than hands and feet’ the God who pervades the universe, to whom the mystical literature of the world bears witness. To deal with this aspect of the Deity, Kabbalah introduces the concept of Emanation and the doctrine of the four worlds. The tradition has it that ‘God wished to behold God’ and in order to facilitate this end, God (the Transcendent) withdrew Itself from a dimensionless point to create a void within which the relative universe could exist. Into this void, which was the first extant thing, the Endless Light of Will (in Hebrew, Ayin Sof Aur) projected itself in ten stages. These ten stages, which are quite unknowable by any ordinary means of cognition, have been variously called ‘The Divine Potencies’, ‘The Ten Crowns’, ‘The Hands of God’, ‘The Garments of God’, ‘The Divine Lights’, ‘The Names of God ‘, etc., in an effort to give some flavour of what they might be like. These ten Divine attributes organized themselves into a design that contained, in potential, all the Relative Universe which was to emerge and all the laws by which it was to be governed. This design, which is the Kabbalistic paradigm for existence, has been represented in various ways; but we will use the configuration called the Kabbalistic Tree of Life.

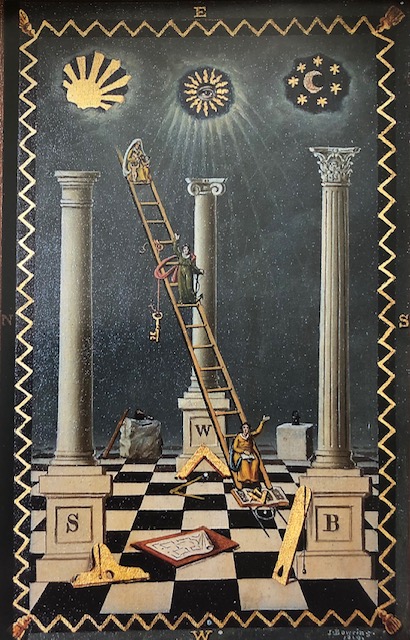

Jacob’s Ladder is a diagrammatic representation of the unconscious connection with Divinity experienced by Jacob in his dream, and it consists of four Kabbalistic Trees interleaved. The Tree of Life is the uppermost of the four (shown in white in this diagram). We will consider the Tree in a little detail in due course. For the moment we can note its major features.

First, it is composed of ten sefirot (shown as circles) which represent the ten original stages of Emanation. These are arranged in three columns: the one on the right active or creative; the one on the left passive or containing; the one in the centre, conscious, or holding the balance between the other two. Sometimes these are called the columns of Mercy, Severity, and Clemency respectively. There are, in addition, four levels. Starting at the bottom of the white tree they are called the levels of Action, Emotion, Intellect, and the Contact with the Source at the top. Lastly, the sefirot are connected by twenty-two paths which define fifteen triads; five related to the active column, five related to the passive column, and five balanced on the Central column of consciousness.

Taken as a whole this white tree, the Tree of Life, is said to represent the world of Emanation the Divine World, The Image of God. Alternatively, it is sometimes called Adam Kadmon, the primordial man. In Hebrew, the name of this Divine World is Azilut, which means ‘to stand near’ because this most subtle and fundamental level of existence stands next to the Deity which is beyond existence. The principles which are implicit in the paradigm of the Tree are the Kabbalistic principles that we seek to examine, but at this level of Azilut they are not immediately accessible to (most of) us as incarnate human beings. For the moment only two more characteristics of the Divine World require our attention. First, although it is called a ‘world’, it is a world quite unlike the one with which we are familiar; it is a world composed entirely of consciousness.

Mystics who experience this world generally speak of it as ‘Light’, and in the ancient Middle Eastern four-element universe this world is symbolized by the element Fire.

The second characteristic is that this world is static. Because it stands in immediate proximity to the Deity and is the image of Deity, it is perfect: and in that perfection, it is perfectly in balance. For example, perfect, absolute Mercy is complemented by perfect, absolute Judgement. This sort of perfect complementary relationship exists throughout the entire Tree so that, although it contains the potential for all things and is the residence for all Laws, there is never an imbalance, and thus, never any motion. In the Christian Tradition, this concept appears in the reference to the “World Without End”. Nothing happens in Azilut; Azilut simply is. However, if the purpose of Emanation is to be fulfilled, Adam Kadmon who is initially in a state of innocence must experience all that can be experienced, and that requires movement. To facilitate that movement a whole new world (actually, a series of new worlds), separated from the perfection of Azilut, but based on its Divine image. The ideas which we have considered thus far are taken from what was originally the Oral Tradition. With the emergence of the first world of separation, we begin to deal with material that is to be found in the Bible. Genesis 1 begins with the words, “In the beginning, God created …”, and this first world of separation is called the World of Creation. The Name of God used in the Hebrew text to describe the creative agency is ‘Elohim’, which is a plural form.

This reference to ‘many Gods’ in the scripture of a fiercely monotheistic religion points us back to the World of Azilut, where it refers to the Ten Divine Agencies through which the Will of God operates to bring the World of Creation into existence. On the diagram of Jacob’s Ladder, where this world is indicated by the light blue colour, this idea is reflected by the fact that the uppermost sefirah of the World of Creation is coincidental with the central sefirah of Azilut. In other words, we can think of Creation as being projected out from the very centre of Divinity. The World of Creation is called Beriah in Hebrew, and as Azilut is a World of pure consciousness, so Beriah is the world of Spirit. The upper portion of the Spiritual world is contiguous with the lower portion of Divinity; they occupy the same space (on the diagram – physical space does not yet exist in this metaphysical scheme); but they are two separate worlds, two different levels of consciousness. Beriah is a world of essences and principles, of ideas.

With this separation from the perfection of Divinity a whole range of ideas come into existence; polarity, good and evil, day and night, past and future (in addition to the fundamental ‘present’), male and female, and with them the concepts of time, imperfection, imbalance and change; the World of Creation is an intensely dynamic world. Creation also contains the essential nature of all those things which are to come into being during the unfolding of the Relative Universe.

For example, in Beriah, we find the ‘Great Cat’. We should resist the temptation to visualize a huge, old, wise, rather avuncular, tomcat because the form of a cat (or indeed of anything) does not yet exist in our cosmological model. Rather we should think of that ensemble of qualities that are the essence of ‘catness’; stealth, curiosity, patience, alertness, subtlety, independence, ruthlessness, etc. This ‘bundle of essential catness’ which is shared to some degree by all members of the feline species is the ‘Great Cat’. A similar ensemble of qualities is to be found in Beriah for each existing thing. Kabbalists place the Four Sacred Beasts, the Bull, the Lion, the Eagle, and the Man around the central sefira of the Beriatic World.

We may think of these as being the archetypal essences of the inhabitants of the four worlds. This first world of separation, the World of the Spirit or of Ideas, is sometimes called Heaven; and it corresponds to Air in the four-element universe. The second chapter of Genesis is very similar to the first, and that similarity tells us something. It says that the same laws and principles which operate in Beriah also operate in this new (third) world that Genesis II describes.

The essential difference between this and the preceding chapter is the operative verb; Beriah was ‘created’ whereas this new world is said to have been ‘formed’. This new world is called Yezirah or the World of Formation; and as Beriah is the Spiritual World, so Yezirah is the Psychological one. Looking at Jacob’s Ladder we see that Yezirah springs forth from the centre of the Spirit, and its upper part is contiguous with (but separate from) the lower part of the Spiritual World in a manner exactly parallel to the relationship between the Worlds of Spirit and Divinity. Note also that the topmost sefirah of the Psychological World is contiguous with the very bottom of the Divine World ‘the hem of the robe of Divinity’ is thought of as the Garment of God.

We will spend some little time talking about Yezirah (which is, as we shall see, the domain of Craft Freemasonry): for the moment we need only recognize that here, in the World of Formation, we find the forms which are assumed by the essences residing in Beriah. To continue with the example of ‘catness’, we find here all the forms a cat might have: a lion, tiger, a tabby, Manx, Siamese, Moggy, etc., forms which are assumed by the feline Beriatic principle. This world, called Paradise in some scriptural literature is the site of the Garden of Eden and corresponds to the element Water in the four-element universe. Lastly, we see the fourth world, the World of Manifestation (called Assiyah in Hebrew) derives from the centre of the Psychological World. This is the physical world with which we are familiar, it is called Earth in the four-element universe, and it is the world entered by Adam and Eve when they were expelled from Eden and given the ‘coats of skin’ (bodies) which the Holy One had made for them.

The study of the Assiyatic World is the business of the physical scientist, and we will have only a little to say about it. It is the World of Manifestation in which we find the specific physical manifestations of the Yeziratic forms of the Beriatic essences. With the emergence of the Physical World, the unfolding of the Relative Universe is complete. Note that all of it (with a single exception) was brought into being original with the Divine act of Creation, the World of Beriah. That single exception is Man who is said to have ‘been made in the Image of God’, to have his origin in Adam Kadmon, in the Divine World.

Man is said to be unique in the Relative Universe in that he, unlike other creatures who were created and are fixed at their respective levels, existed before Creation and can be conscious of – and operate in all four worlds. Indeed, that is his responsibility. An individual human being is said to start as a spark of consciousness in Azilut, to descend to Beriah where it is wrapped in a Spirit, thence into Yezirah where it is clothed in a Soul. There it waits for its moment to incarnate at which time the individual starts his journey back through the levels of consciousness until he returns once again to Azilut carrying his portion of the experience. The tradition has it that when the last soul has completed this journey and resumed its place, Adam Kadmon will have experienced all things, and God will behold God in the Mirror of Existence.

Before we move on to a more detailed consideration of the Tree of Life as it is found in Yezirah we should note a few additional things about Jacob’s Ladder. First, the use of the same diagram (the Kabbalistic Tree) to describe each world is significant. It indicates that the same laws operate in each world, they simply operate at different levels. This is a diagrammatic statement of the succinct metaphysical principle, “As above, so below”. Next, note that this scheme (which is relatively straightforward neo-platonic metaphysics and the foundation for almost all Western thought on the subject) was expressed in a very interesting way by Ibn Gabirol and Ibn Latiff, both Spanish Kabbalists writing in the l1th\13th centuries. In trying to describe the generation of, and the relationships between, the four worlds they used the notion of a point moving to create a line; the line moving (in a direction not parallel to itself) to create a superficies; and the superficies moving in a similar way to create a solid. Each of these geometric figures is new but contains within it the essential qualities of, and access to, the figure from which it derived. We note that both man and the universe are thought to be made in the Image of God so that the Tree of Life can be thought of as a diagram of an open system. Kabbalists use it broadly as a conceptual diagram of the entire Spiritual World or specifically as, say, a model of the human psyche; and throughout this paper, we will refer to it in both its broad and specific contexts. Because of this characteristic – the fact that the Tree is a single diagram that can be used to represent many things – it is very important when using it that one specifies exactly what the Tree is being used to represent. We will say more about this later.

Finally, we might recognize that if we present this sort of idea to a contemporary academician, we will be told that it is a form of teleology that typifies old-fashioned efforts to prove the existence of some ultimate cause using the wonderful structure of the physical world as an argument. This sort of reasoning, he will tell us, is demonstrably unsound. That may be so, but for the Kabbalist, the academic objection is irrelevant because he does not use this metaphysical system to prove the existence of God. Traditionally the Kabbalist has been a practitioner of what is being called Consciousness Research in contemporary academic circles (although the Kabbalist has always conducted his work in a religious context). The important point is that the Kabbalist’s work is empirical. In the last analysis he does not believe, he seeks to experience. The ideas set out in Jacob’s Ladder (or in the ‘regular progression of science’) comprise a hypothesis on which the Kabbalist bases his work, a map if you like, by which he will travel from West to East through the levels of consciousness. Like all travellers, he must start his journey from his present location; and for most incarnate human beings that implies starting with a study of the psyche.

Psychology

Reference to the diagram of Jacob’s Ladder shows that Yezirah, the Psychological World is intimately associated with both the spiritual World of Beriah and the Physical World of Assiyah. The lower face of the psyche and the upper face of the Physical World overlap and occupy the same space on the diagram and is in keeping with ordinary experience. Indeed, the feeling that the psyche is infused throughout the body is so common and so strong that many people cannot recognize the two as separate things. The diagram also indicates that the very top of the Psychological World touches the lowermost point of Divinity. Thus, we can see that in its most general context the psyche of an incarnate human being is a sort of bridge of consciousness between the Physical and Divine Worlds. The Tree of the Psychological World is shown in some detail on the facing page, and we can use this Psychological Tree (which is more accessible than the Tree of Azilut) to gain some insight into our own nature and to obtain some glimpse into the nature of Divinity. In doing so we will be applying the Greek maxim ‘Man know thyself, and you will know God’. To put it another way, we shall ‘find out the contents of bodies unmeasured by comparing them with those already measured.’ Looking at the Psychological Tree we observe that it is identical in form to the Divine Tree, and in considering its characteristics we can identify some of the major laws which are said to govern all the Relative Universe. First, there is the Law of Unity; although it is composed of numerous elements, the Tree itself is a single, integrated whole; a system, so to speak. (This notion of a ‘garment without a seam’, which actually applies to the entire relative universe, maybe the first formulation of the principles of systems theory).

Second, is the Law of Opposites (or Complementarily). The Tree is symmetrical about its vertical axis, each active, positive, or masculine component is offset by a corresponding passive, negative or feminine component.

Third, is the notion of dynamic stability achieved by a conscious agency holding the two opposing functions in balance (called the Rule of Three in old Masonic workings), represented by the three columns of Mercy, Severity, and Consciousness.

Fourth, is the structural concept of four levels (action, emotion, intellect, and contact with the Source). We can note also the fifteen triads formed by the paths between the ten sefirot. At the level of the psyche, these last are more or less directly accessible (as they are not at the level of Azilut), and we can examine them and begin to fill out the framework of the Tree.

Since comprehension is often easier if we can relate abstract ideas to our experience, we will start at the bottom. The bottommost sefira is named Malkhut, the Kingdom. It is coincident, on Jacob’s Ladder, with the Tiferet of the Physical World which, in terms of the human body, is equated with the central nervous system and the associated organs of Perception. Thus, we can think of the Malkhut of Yezirah as being that part of the psyche which is in direct contact with the physical body. In this connection, one of Malkhut’s functions is to select the data which is presented to the psyche from the Physical World and to structure it into a form that can be interpreted by the psyche. It accomplishes this filtering by the use of sense organs which are highly selective to physical stimuli. Thus, we see the central nervous system in the Physical World and the Malkhut of the Psychological World, as acting together to form the hardware interface between the individual’s body and the psychological being that occupies it.

The next sefirah is Yesod, the Foundation. In the most rudimentary terms, Yesod is the psychological capacity to form images, and thus it forms a sort of ‘screen’ upon which the perceived phenomena can be observed. We should note these phenomena may be based on events in the Physical World or upon material from deeper in the psyche. The process of image formation is fundamental to almost all psychological activity, and it is for this reason that the capability is called the ‘Foundation’. In human beings, this capacity for image formation results in an apparently unique phenomenon; the ability to form an image of the individual himself. In the terminology of contemporary psychology, this self-image is the ego, and it develops during early childhood as the infant starts to form a sense of itself, separate from the world around it. As we will see, we are using the term ‘ego’ in a sense very similar to the meaning which Jungian psychologists attach to the word. As an image of the individual’s real nature, the ego is probably (almost certainly) less than accurate because it is concerned with the immediate task of relating the individual to the world; but in any case, the ego is the routine supervisor of the day to day psychological activity; and it determines (by its capacity for image formation) those things which are to be admitted to consciousness.

The third sefirah is Hod. In the past, ‘Hod’ has generally been translated as Splendor, but in some ways, that word is not very instructive. The Hebrew word means to ‘shimmer’, or ‘resonate’, or ‘reverberate’ and Reverberation (or perhaps Resonance) may be a more instructive translation. The first thing to notice about Hod is that it is on the side column of constraint, thus it represents a psychological function (in contrast to sefirot and triads on the central column which relates to levels of consciousness). The second point about Hod, which fixes it precisely on the Tree, is that it is at the lowest of the four levels, the level of psychological action. In terms of our everyday experience, the psychological function of Hod represents the capacities for mentation; thus, calculation, analysis, classification, storage and retrieval of data, communication, and the general manipulation of information are all examples of Hodian psychological processes. In the human experience these abilities usually develop between the ages of between 6–7 and 13–14, although they are powerful psychological tools, they are essentially superficial ones. That is why pre-adolescent children (and adults who continue to operate at this stage) may be clever but are seen to lack depth.

The sefirah which complements Hod on the active side pillar is Nezah, Eternity. (The popular 19th-century translation was Victory, but again, that English word is not a particularly pregnant one.) Eternity is not particularly good either until we think of it in terms of endlessly repeating cycles, which contains the notion of enormous energy and boundless passion. Indeed, Nezah which is the counterbalance for Hod is experienced as the energy input into the psyche; and in the normal human development, this capacity for the conscious experience of passion begins to emerge during adolescence say between 13 – 14 and 20 – 21. It is important to realize the Nezahian capacity for the experience of passion and the physical capacity for sexual reproduction, which normally develop concurrently, are actually two quite different (although related) phenomena. Nezahian passion is a psychological function that operates in Yezirah and is far broader in its scope than simple sexual interaction; it may manifest as an artistic capacity, a dedication to a cause, or a commitment to an ideal as easily as in a romantic relationship. Sexual reproduction, on the other hand, is a phenomenon associated exclusively with the Physical World. A glance at the diagram of the Tree will indicate that when the sefirah of Nezah has emerged into awareness, one has conscious access to all of the great lower triads which contain three smaller triads clustered around the ego at Yesod.

This great lower triad contains the ordinary psychological capacities consciously available to most people. These are coordinated by the ego; and one can call them the ability to act (which is represented by the Malkhut-Nezah-Yesod triad); the ability to think (represented by the Malkhut-Hod-Yesod triad); and the ability to feel (represented by the Hod-Nezah-Yesod triad). The path between Hod and Nezah represents the threshold of ordinary consciousness and for the vast majority of people, the remainder of the Tree beyond this threshold remains outside their conscious experience (in the unconscious, to use the psychological term) except under the most unusual circumstances.

This general level in the lower part of the Tree, centred on ego/Yesod corresponds broadly to the individual consciousness of Jungian psychology. On occasion – and the tradition has it that such an event occurs at least once in every lifetime – circumstances occur that project the individual’s consciousness across the Hod-Nezah threshold into the triad of awakening and give them access to Tiferet.

Tiferet is the central sefirah of the Tree, and it occupies a special position. The special nature of Tiferet’s position derives from two sources; the first is its location in the Tree. As the central sefirah, it is the focus of things; nine of the ten sefirot and eleven of the fifteen triads are in direct contact with Tiferet. Thus, Tiferet is, in a sense, the essence, or blossom, or fundamental resultant of all the other components of the Tree. This characteristic of containing and displaying the qualities of the whole organism is conveyed by Tiferet’s English translation, Beauty or Adornment (sometimes Truth). From the psychological point of view, we can think of Tiferet as being equivalent to Jung’s concept of the Self. From its central location, we can see that an individual whose consciousness is centred in Tiferet is in a very different situation from one who is operating from Yesod. The former has direct access to all the sefirot except Malkhut and to almost all the material in the triads in the upper part of the Tree (in what is usually the unconscious) as well as the lower part of the Tree through Yesod. In contrast, the person operating from Yesod has access only to the three triads of acting, feeling, and thinking, and the sefirot of analysis, passion, and sensation. The second thing that is special about Tiferet’s location is its position on Jacob’s Ladder.

A glance at that diagram will show that Tiferet’s position at the centre of the Psychological World is, at the same time, at the topmost point of the Physical World and at the Malkhut of the Spiritual World. The person who occupies this place where the three lower worlds intersect can be centred in his psyche, in complete control of his physical vehicle, and open to the influence of the spirit through the ‘Kingdom of Heaven’. In this context, the name, Beauty, takes on an additional meaning as the Self of the individual is seen to be a reflection, first of the Tiferet of Beriah, and ultimately of the Creator at the Tiferet of Azilut. For this reason, Tiferet is sometimes called the ‘luminous mirror’ and the whole idea is another reminder that an individual human being is made ‘in the image of God’.

Before we go on the examine the upper parts of the Tree, we must consider one more feature connected with Tiferet; the path between Tiferet and Yesod. This path is called the Path of Honesty, and its name suggests that by being scrupulously honest with one’s self one can open the access from Yesod to Tiferet so that one can awaken and occupy the Tiferet position at will instead of waiting to be thrust into it by an act of Providence. On the side pillars above Tiferet one finds the complementary sefirot of Gevurah (on the passive pillar) and Hesed (on the active pillar). As Hod and Nezah are found at the level of Action so these sefirot are at the emotional level; and as they are on the side pillars, we can see that they represent psychological functions. The word Gevurah means Strength or Justice, and one should recognize that it includes a constellation of related constraining concepts such as rigour, discipline, discrimination, precision, constraint, condemnation, support, and containment. In a similar way, Hesed (the name means Mercy) includes such concepts as giving, forgiving, kindness, largesse, license, and freedom from restraint. The names Justice and Mercy, also have a moral quality; and here, in the Triad of the Soul (formed by the sefirot of Tiferet–Gerurah–Hesed), one finds the residence of the individual’s capacity for morality. The soul triad is one of those triads which are centred on the central column; and thus, it is a triad of consciousness.

As we have seen, most people who operate from Yesod do not experience the soul directly. It continues to operate, however, in the unconscious; and most people are dimly aware of it, and its guiding activities, as the prompting of conscience, find their way to the ego from the unconscious. The person who is able to operate routinely at the level of Tiferet has direct access to these sefirot of morality, and it is their responsibility to make conscious use of the functions of Justice and Mercy, and in doing so to keep them in balance.

At the top of the two side pillars, we find the uppermost pair of complementary, functional sefirot. They are named Binah, Understanding, and Hokhmah, Wisdom. Being in the upper part of the Tree, these sefirot relate to the intellectual level and to psychological functions which, while available to the individual, are also shared by the entire human race. This transpersonal level of the psyche is very generally equivalent to the Collective Unconscious as defined by Jungian psychology. Binah refers to Understanding at the most profound level. We can think of it as the residence of law, tradition, of a fundamental principle which is to be comprehended only after long and patient study at the end of which one says very quietly, with a sigh, ‘Ah, at last, I understand’.

Hokhmah is quite the opposite. Situated on the active column at the level of intellect, it represents the function of revelation, the place of the prophet. Referring to the diagram of Jacob’s Ladder, we see that Hokhmah underlies the Beriatic Nezah; and we might expect this to be a sefirah of great power. It is, in fact, the place where the spirit, entering the Psychological World, first takes form; and when one has an Hokmahian experience it comes as a sudden flash of insight that strikes the very core of the situation. It frequently shatters one’s most cherished illusions in the bargain, in contrast to the sigh of Binah, Hokhmah is recognized with a gasp.

A note on terminology might be appropriate. We have been using terms such as ‘in Tiferet, ‘access to the sefirah of Nezah, and ‘in the Triad of the Soul’ and these may seem strange, if one looks at the diagram and asks oneself, ‘Why in that triangle?’ or ‘What do they expect to find in that circle?’ One should interpret the expression as a shorthand for something like, ‘in the state of consciousness in which one can perceive accurately’, ‘access to the capacity to experience passion’, or ‘the psychological space bounded by the functions of judgment and mercy and the conscious capacity to determine truth’. In a similar way, the phrase ‘in the passive emotional triad’ is a convenient way of saying ‘in the psychological space bounded by the capacity to determine truth and the functions of constraint and analysis’.

Before we complete our analysis of the Tree with a consideration of the topmost sefirah we must touch briefly on some of the triads which are formed by Tiferet and the six functional sefirot on the active and passive pillars.

Four of these triads are related to the side pillars: two active and two passive. The lower of the two pairs (i.e. Hod-Tiferet- Gevurah and Nezah -Tiferet-Hesed) are at the emotional level of the Tree, and they contain (schematically) memories of emotionally charged experiences. These memories (frequently unconscious) affect our behaviour profoundly, and those associated with emotions that move us to action are to be found in the active triad while those which constrain us are stored in the passive triad. On the diagram of the Yeziratic Tree, these are labelled Active and Passive Emotional Complexes after the usage of Jung who recognized that these emotional memories were highly inter-related, frequently in very complicated and subtle ways. In a similar way, but at the intellectual level, we find the upper pair of triads (Gevurah–Tiferet–Binah and Hesed–Tiferet–Hokhmah) which are labelled Active or Passive, Intellectual Complexes.

These contain the very profound ideas, which most of us are likely to take for granted, upon which we build our concept of the world. These ideas generally derive from our culture but are often shared by the entire race. For example, a man raised in a Roman Catholic culture will have, as part of the fabric of his intellectual frame of reference, the idea that one can marry only one woman and that, having done so, one can never be divorced. This idea (and many related to it) will reside among his passive intellectual complexes, and it will constrain his behaviour considerably. He is unlikely to give it a thought, however; unless, perhaps, he meets a Muslim who has quite different intellectual complexes relating to this subject. Among the active intellectual complexes, we find, in those raised in the western democracies, concepts relating to representative government and due process of law. Their willingness to die for such concepts is a sure indicator of the power of the material which is stored in these triads. A person whose consciousness is centred at the level of ego/Yesod is driven by these active and passive emotional and intellectual complexes, the operation of which they, at best, are only dimly aware. They do not have much real choice in their actions, and the capabilities represented by the sefirot are limited and distorted by the demands of the stored ideas and emotions.

A person who can, even to a small extent, centre his consciousness in Tiferet (by being honest with himself) begins to see these emotional and intellectual complexes as they are and to understand their working. For such a person the emotional charge and the cultural authority drains out of these complexes. They remain as memories, as experiences available for use when they are appropriate, but they no longer compel behaviour. A person whose consciousness is centred in Tiferet and who works at the level of the Soul has access to the triad of the Spirit (Binah-Hokhmah-Tiferet) which is balanced on the column of consciousness and is concerned with the transpersonal level of psychological activity. Such a person also has access to the non-sefirah of Daat (meaning Knowledge) which we will have a good deal to say later.

For the moment we need only say that Daat does not exist as a sefirah in Yezirah, but a glance at Jacob’s Ladder indicates that at the corresponding place in the next world we find the Yesod of Beriah. Here is an interface between the worlds which we will consider in due course. The topmost sefirah is Keter, the Crown. It is the source from which the psyche comes into existence. In Jacob’s Ladder, it is located at the point where the three upper worlds meet. Thus, it is, for the incarnate human being, the entry point to the Heavenly Jerusalem (at the Tiferet of Beriah) and the contact with Divinity at the place of the Shekinah. The objective of the Kabbalist (as distinct from the occultist using Kabbalistic methods) is to be of service to the Holy One by bringing this whole Tree into their consciousness and under their control; thus establishing the continuity of consciousness through all the worlds by recovering the connection with Divinity which mankind lost when it was expelled from the Garden of Eden (projected into physical incarnation). This task is called, in Kabbalah, the work of Unification.

This is a brief, very simplified, but reasonably complete thumbnail sketch of the basic elements of the Kabbalistic system expressed in more or less contemporary terms. What remains is to relate it to our own lives. It is of little benefit simply to learn the concepts as concepts. What we have to do is, first, to become thoroughly conversant with the principles, second, to observe the principles in our day to day life, and third, to make the practice of these Kabbalistic principles part of the fabric of our life so that we can stand and behold the Holy One as He lives His Life through us.

© W. Kirk MacNulty